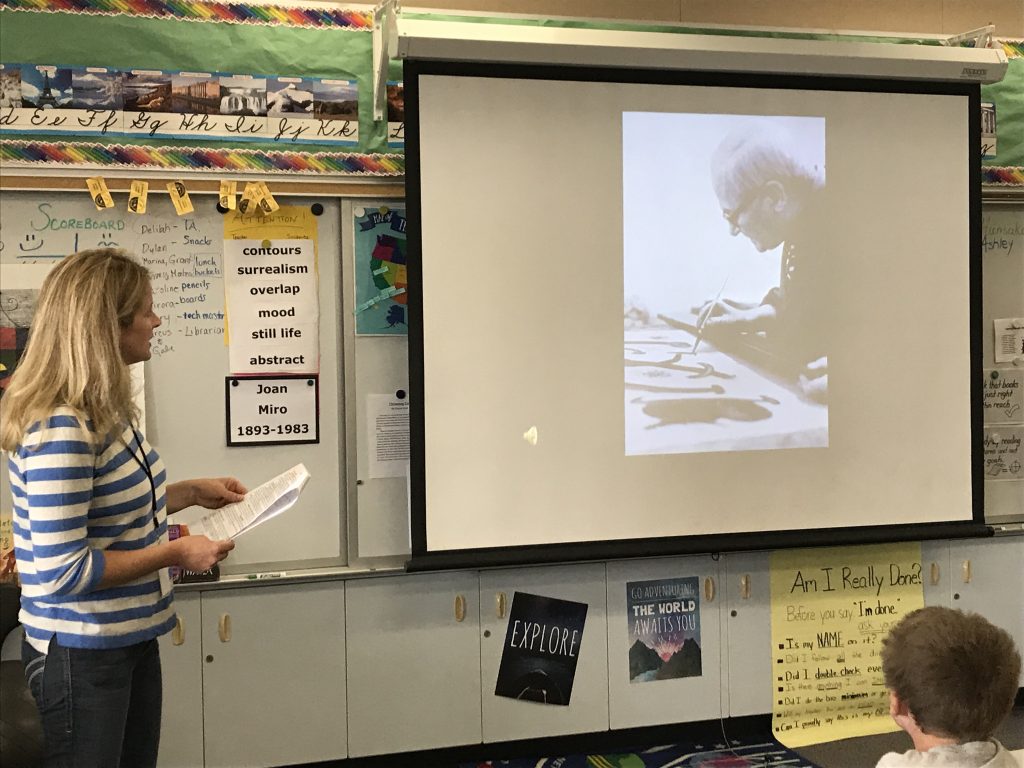

Spanish painter Joan (pronounced Juan) Miró (1893-1983) was a painter who third graders could relate to; unlike some artists, whose works were picture perfect and realistic, Miró thrived on imperfection, actually preferring to start each artistic endeavor with a mistake. When a blob of paint would accidentally make its way on to a blank canvas, Miró, a surrealist, would turn that singular blob into a fantasy masterpiece.

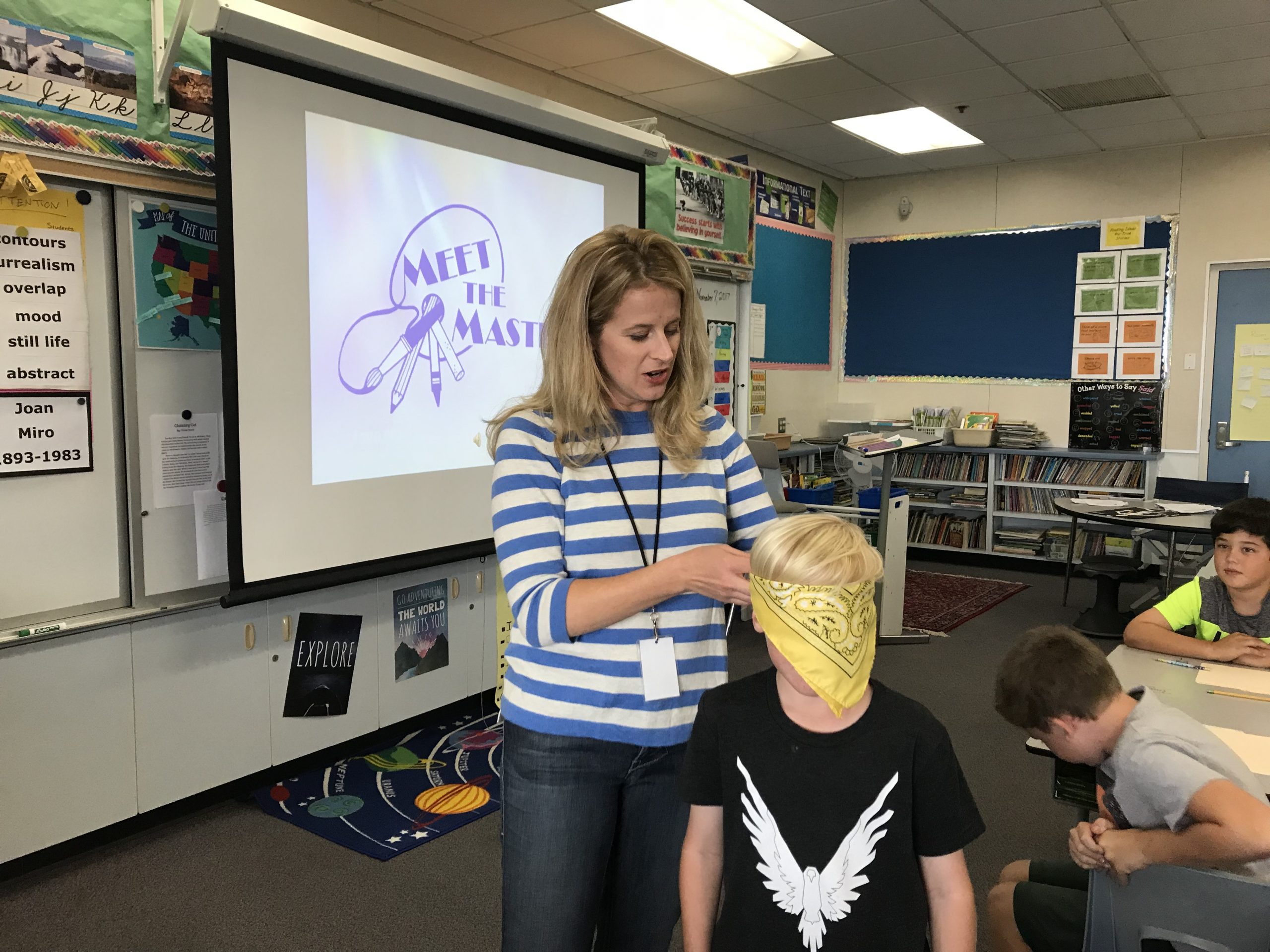

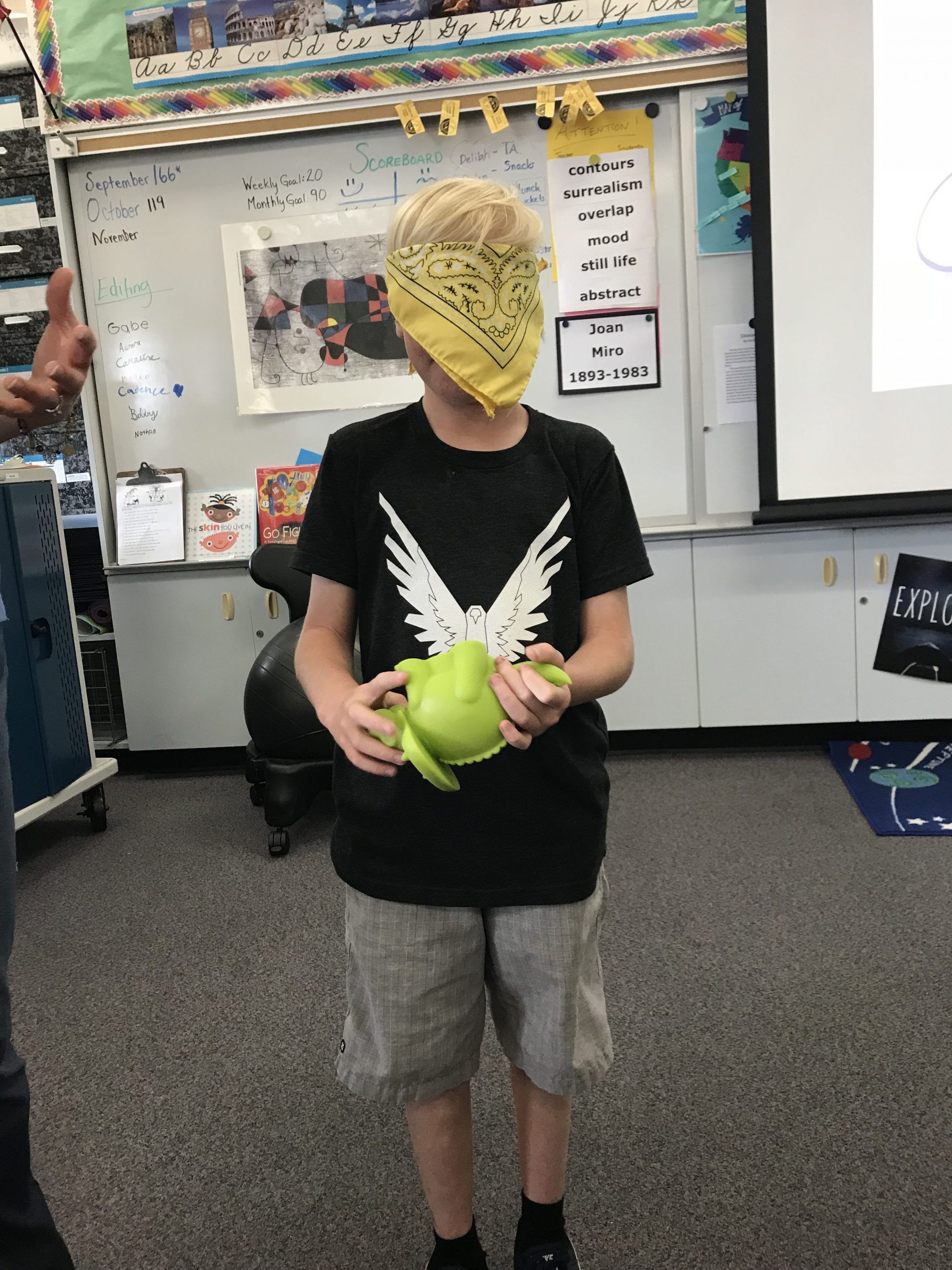

As the first half of the art lesson, led by two parent volunteers, began, an adventurous student graciously agreed to be blindfolded in front of the class. The parent volunteers shed some light on Miró’s rather unorthodox art education, in which his mentor would cover young Miró’s eyes, encouraging his protégé to use other senses as he painted, especially touch. The blindfolded student was given an unknown object, and when asked to identify that object through sense of touch, he, much to the hushed class’s amazement, was eventually able to correctly determine he was holding a rhinoceros. Students learned that when Miró was blindfolded, he, just like their blindfolded classmate, would feel the contours and shapes of objects his instructor placed in his hands, and without ever seeing those objects, Miró was expected to draw them.

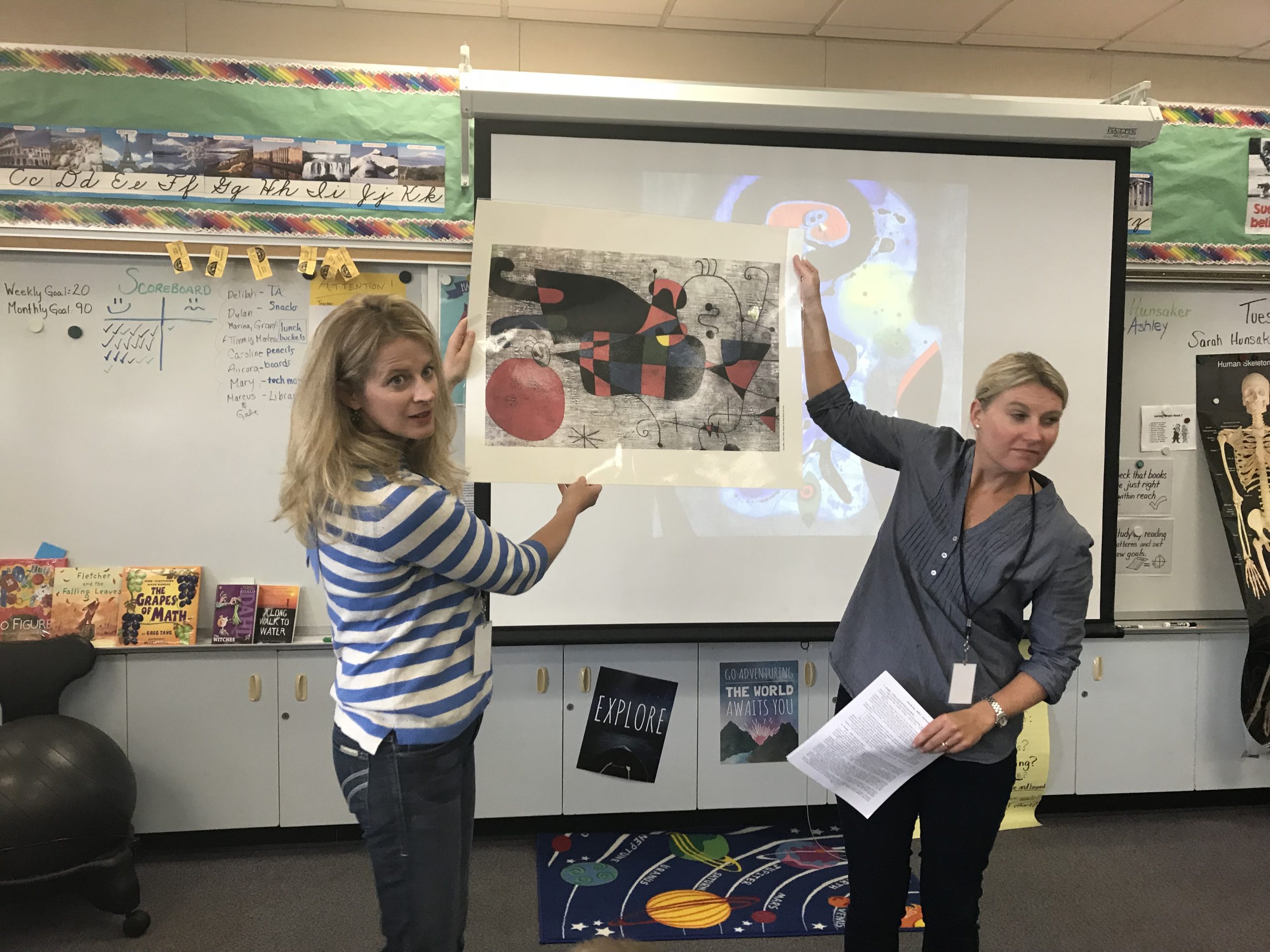

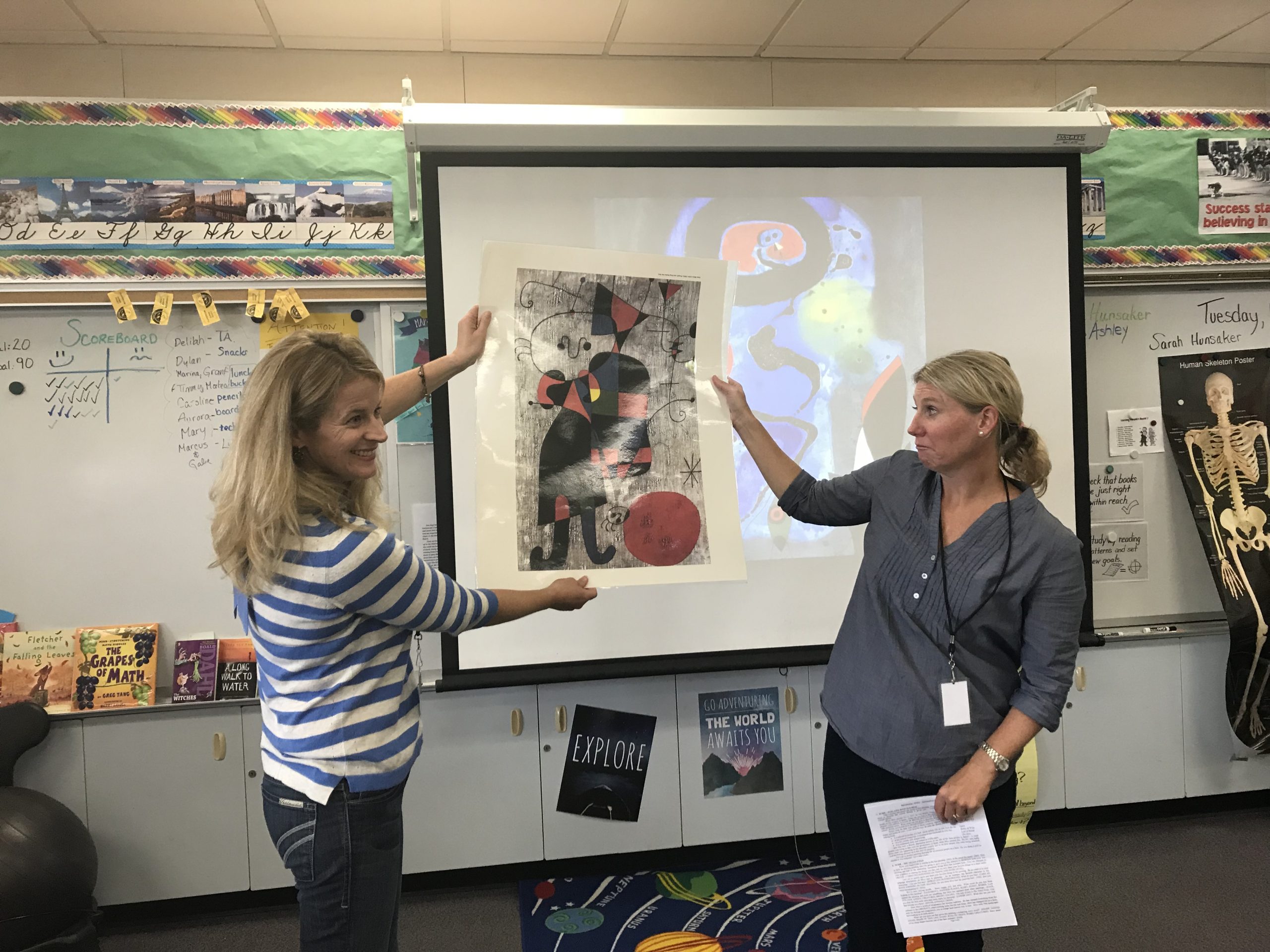

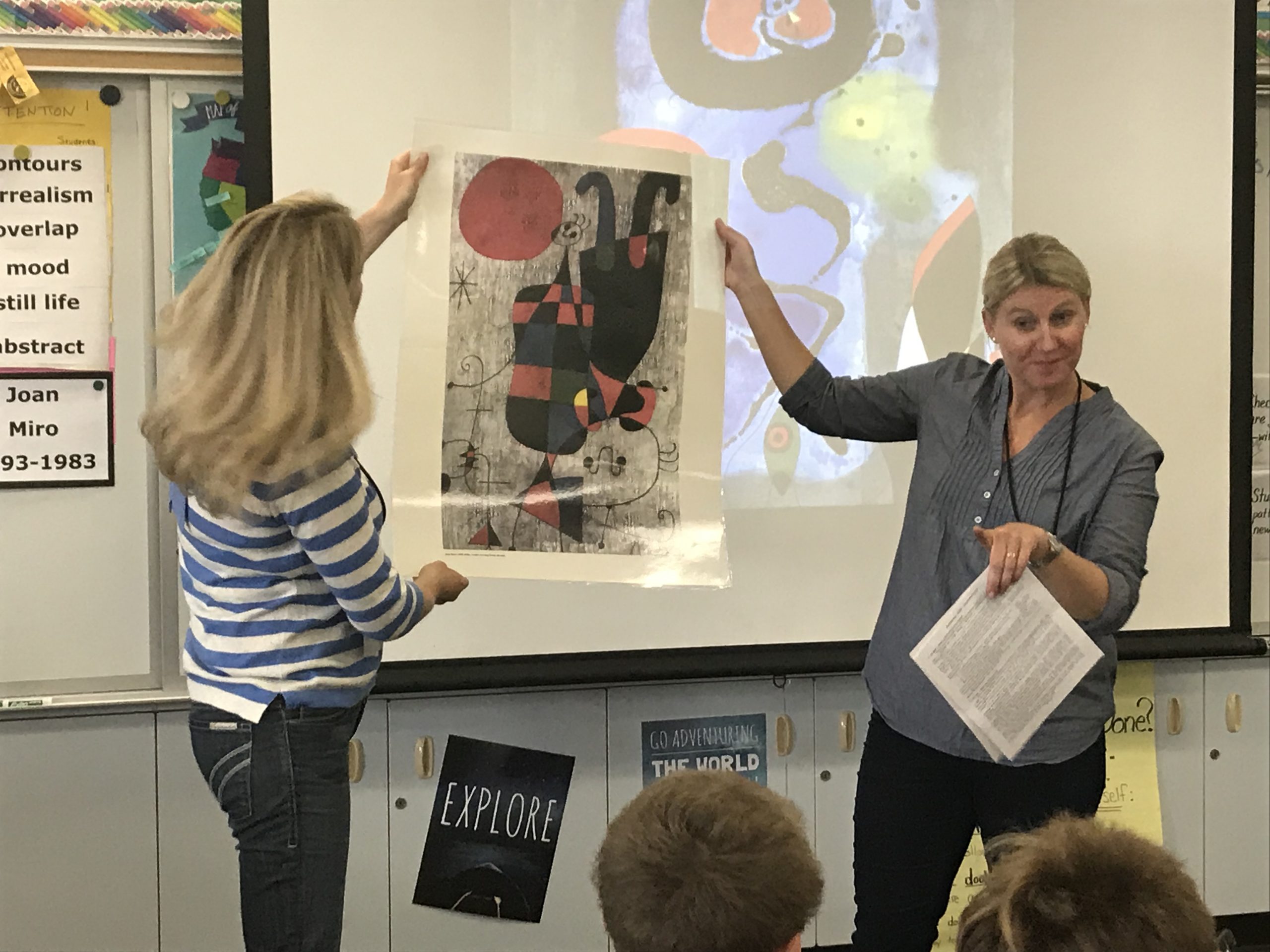

As an abstract artist, Miró’s artwork depicted dreamlike visions in which there was often much room for interpretation. As the parent volunteers encouraged students to study Miró’s 1949 piece Figures and Dog in Front of the Sun, they were asked to consider which way was the “right” way to showcase the artwork. As they rotated the poster of his famous work, students quickly discovered that the painting could easily be hung a number of ways.

Learning about abstract art, students were exposed to the idea that when it comes to abstract art, rules don’t apply! Nothing needs to look realistic, objects don’t need to be drawn to scale, and any color goes! While a realistic painting might not necessarily evoke a mixed reaction from most third graders, as they studied Miró’s paintings, they discussed the mood of each piece, recognizing that while one student felt one particular emotion as he looked at a piece, another classmate felt something else entirely. Abstract art, they learned, is particularly interesting because there is so much room for interpretation on a number of levels. While one student looks at an abstract painting and sees a dog, another student may look at the same painting and see an inanimate object instead.

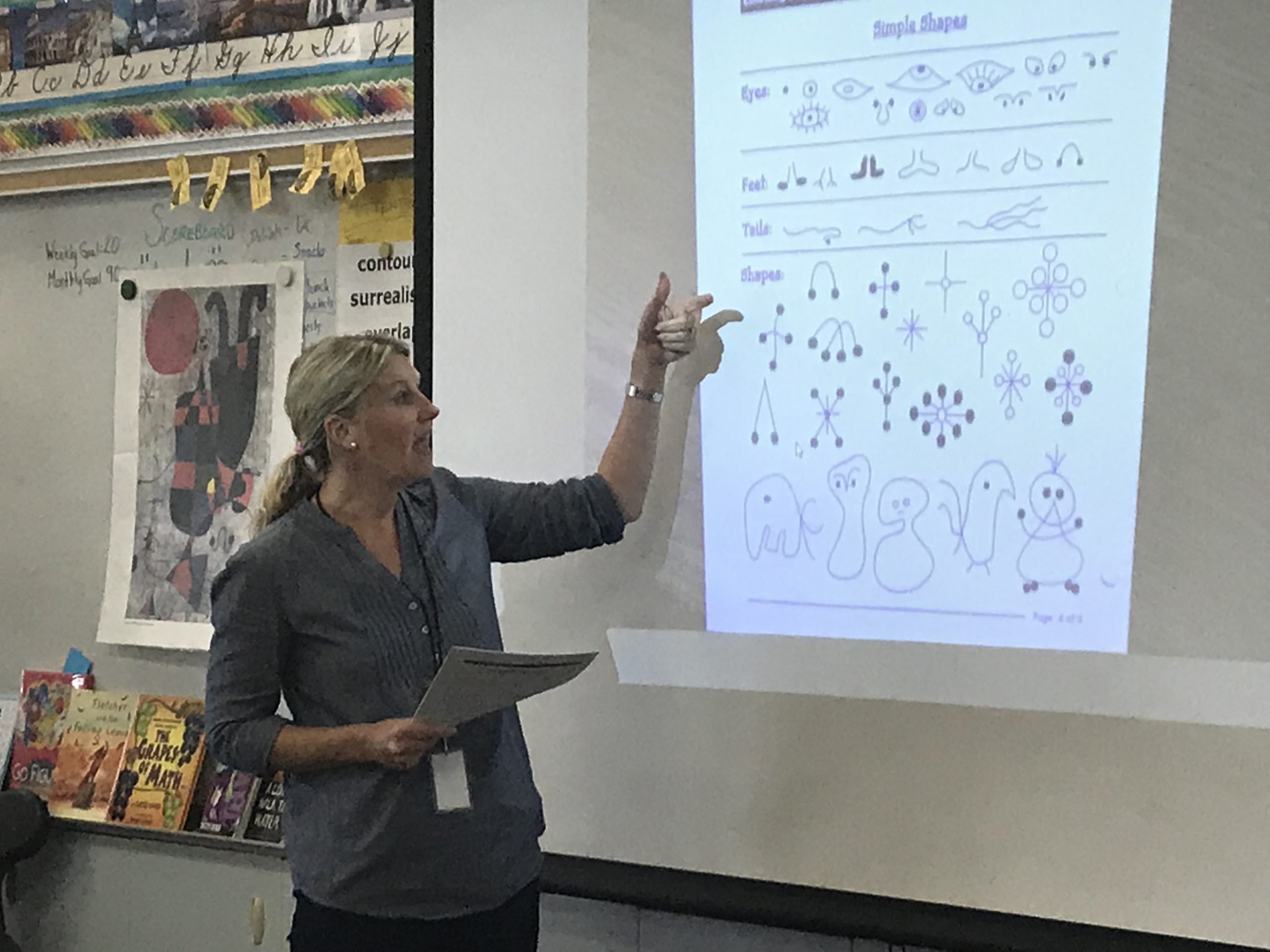

During the second part of the Miró lesson, students reviewed important art vocabulary words they focused on during the first lesson, such as contours, surrealism, overlap, mood, and abstract. As they prepared to create their own abstract artwork inspired by Miró, the most important detail about him that they recalled was that he loved mistakes. As a third grader, what could be better than creating artwork where there’s no chance of messing it up? How often in their lives are mistakes actually encouraged?

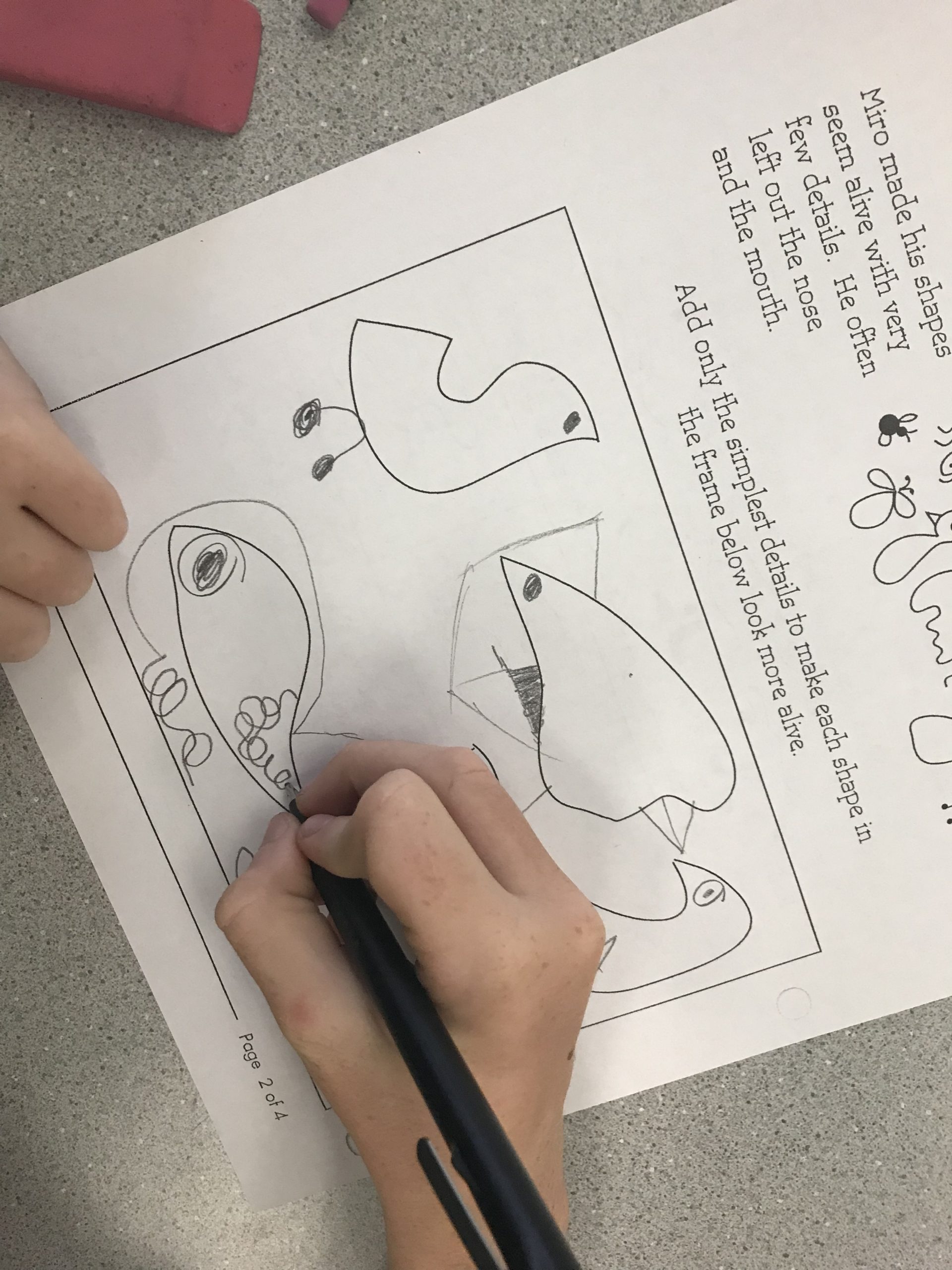

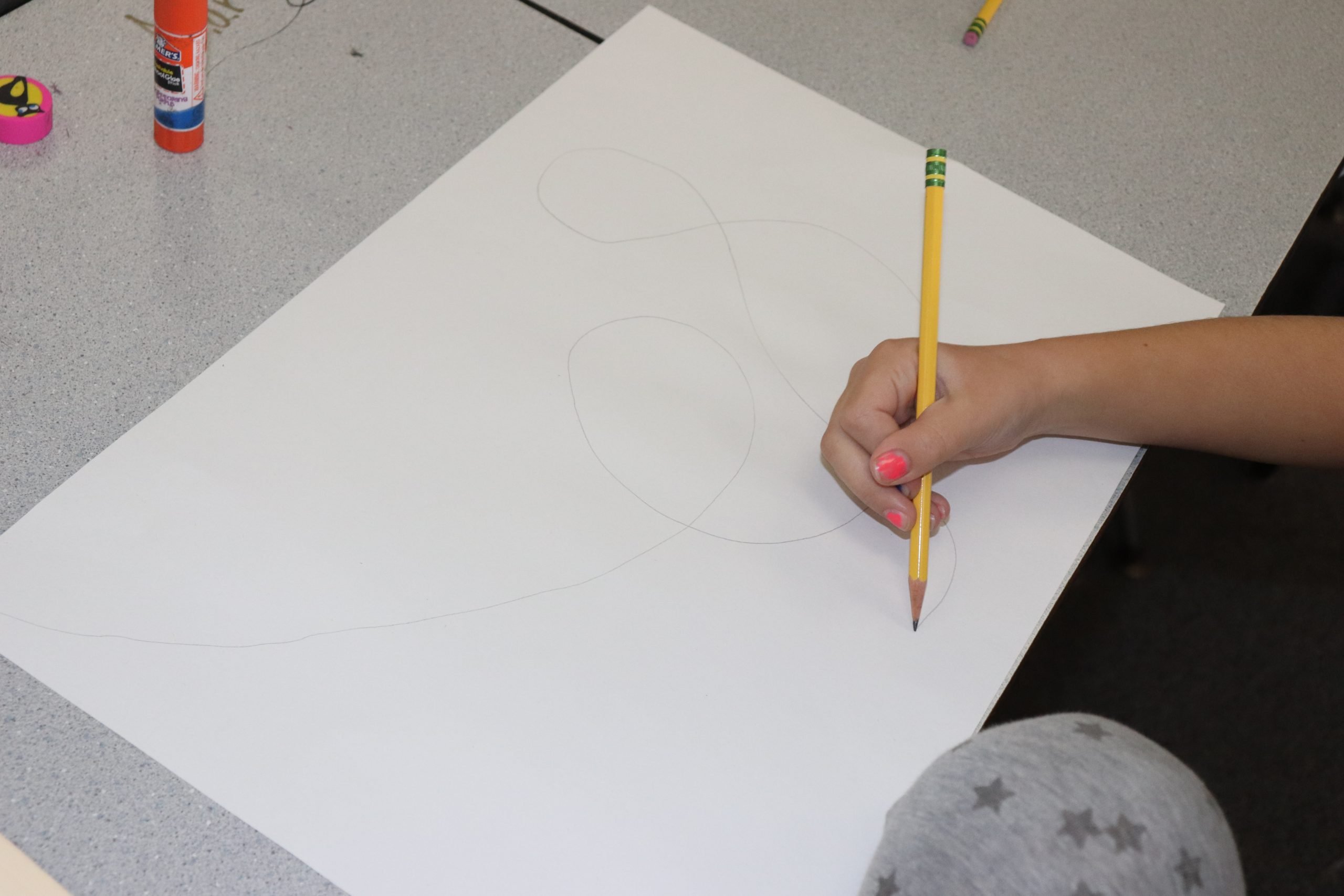

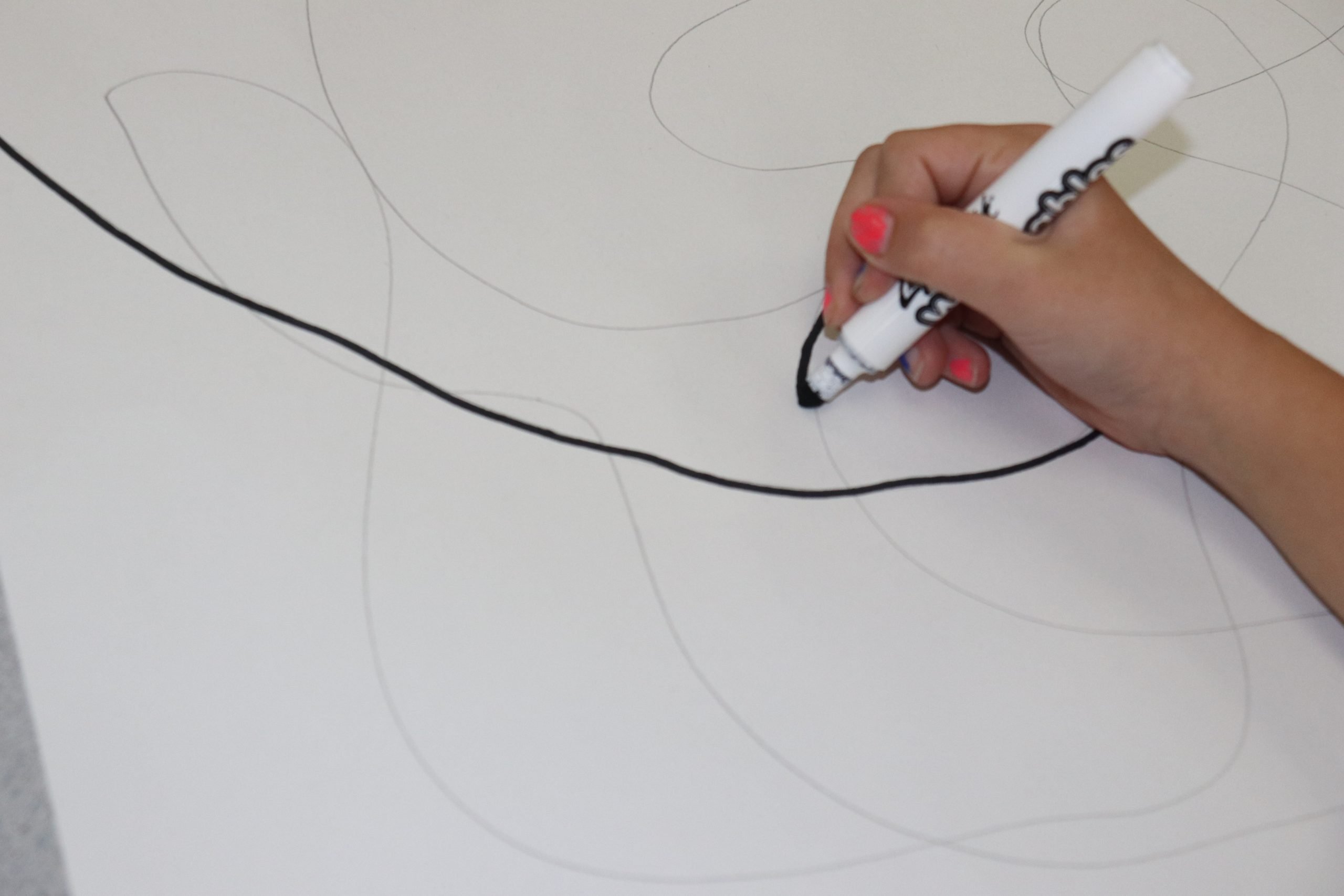

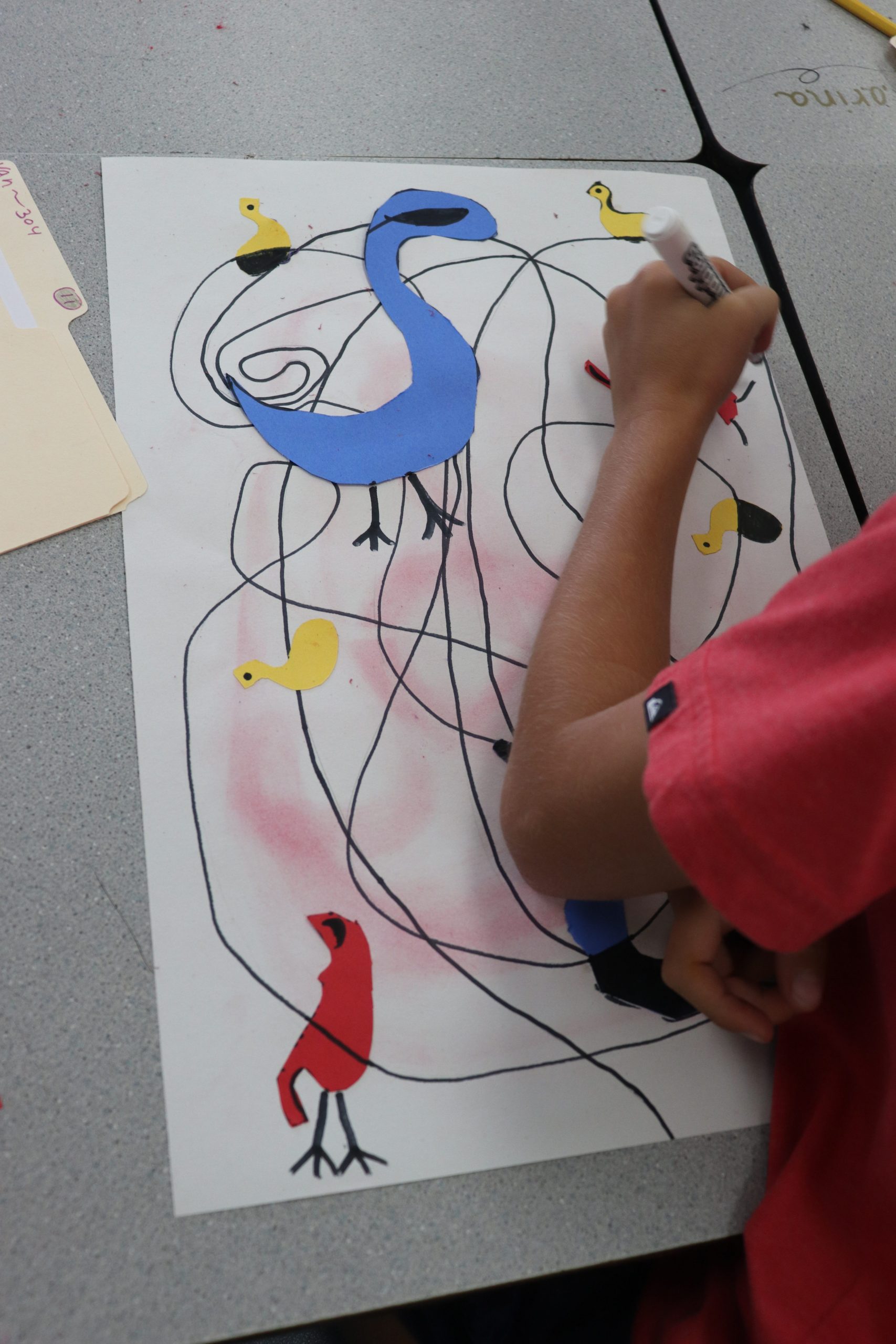

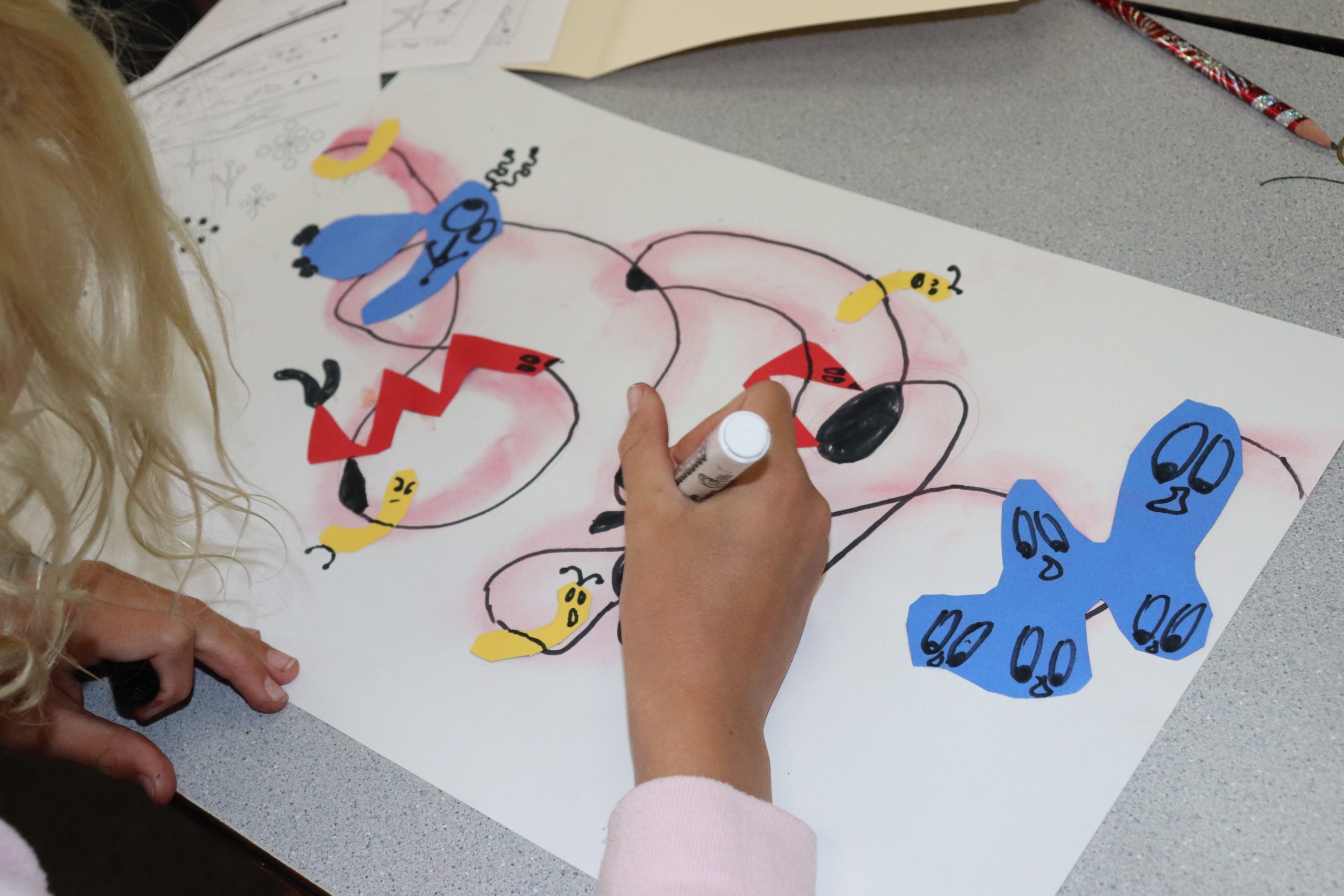

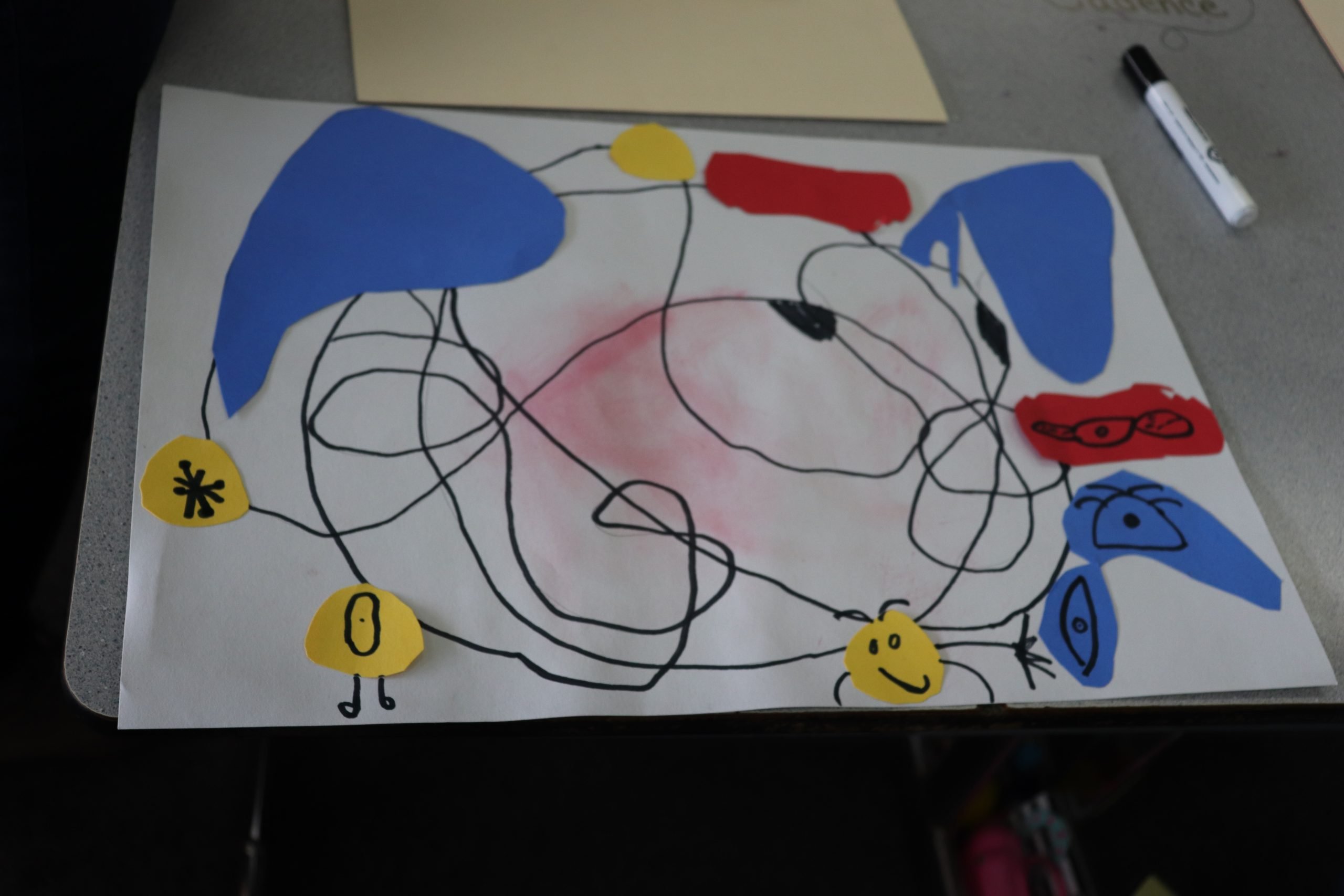

Students were given a blank canvas of their own (white construction paper) and asked to use pencils to draw dreamy lines that swirled on their pages. With black markers, they then traced over their lines. Next the students used cotton balls dipped in red powdered tempera paint to create contours like Miró did. Using blue, yellow, and red construction paper, students drew and then cut out irregular shaped figures of various sizes.

Students were encouraged to place the shapes on their “canvases” before applying glue, and as they decided where each piece would be thoughtfully placed, they were persuaded to think about balance. After shapes were securely glued to the white construction paper, students added more black lines, overlapping some of the shapes. Utilizing their practice sheets from the first lesson, students applied abstract elements to their artwork, including playful eyes and feet. They also used their black markers again to shade in specific areas of their choosing.

As students completed their lesson on Joan Miró, they couldn’t help but compare their masterpieces with one another. Even though they all followed the same set of instructions, they marveled how none of their pieces looked alike. One student proclaimed, “Miró would like that! He wouldn’t have wanted our work to be the same!” That one simple yet profound statement, summarized the lesson perfectly. In a world where children are taught to strive for perfection, the lesson on Miró was not only important in terms of art history and appreciation, it was a powerful reminder to students that they’re allowed to be creative sometimes without needing to follow the rules. Life isn’t perfect, and their artwork doesn’t have to be either!